Heat Transfer Explained Simply: Everyday Examples of Conduction, Convection, and Radiation.

Heat Transfer Explained Simply: Everyday Examples of Conduction, Convection, and Radiation.

Heat Transfer Explained Simply: Everyday Examples of Conduction, Convection, and Radiation.

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!How Heat Transfer Really Works: Simple Insights for Daily Life

Heat transfer is part of nearly everything we do, from cooking breakfast to keeping tea hot on a cold morning. Understanding how heat moves helps us make better choices at home, in the kitchen, and even while outdoors. The science behind these everyday events centers on three main ways heat travels: conduction, convection, and radiation. Learning about each makes it easier to see the science in action all around us, from a sizzling pan to a steaming hot cup of coffee or a perfectly insulated thermos.

The Three Types of Heat Transfer

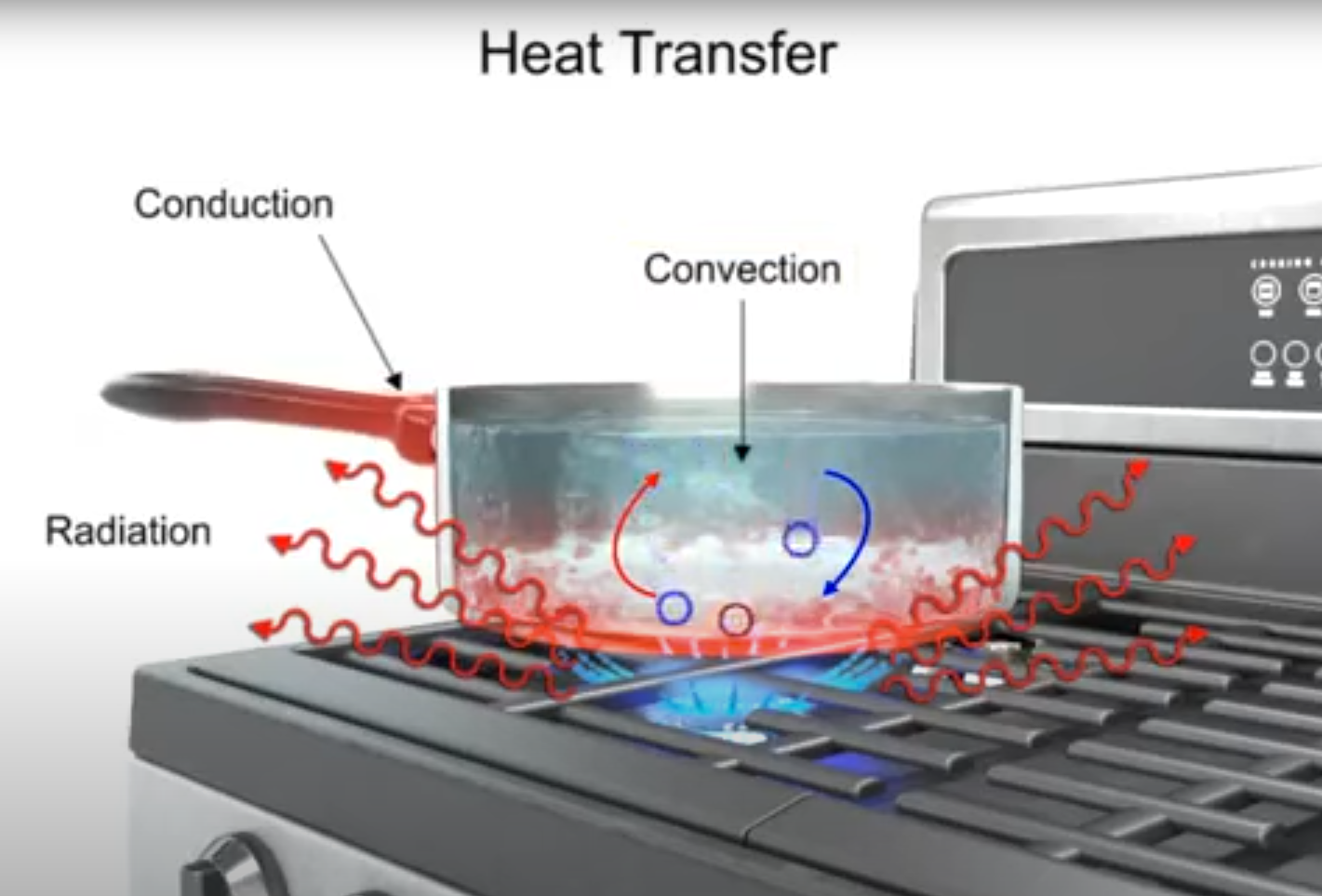

Nearly all heat moves through conduction, convection, radiation, or some mix of the three. These processes shape how we cook, stay warm, or keep things cool. Let’s break down each kind and see what makes them unique.

Conduction: Heat Through Direct Contact

Conduction is the movement of heat through materials that are touching each other. Think of a metal pan resting on a hot stove. Here, heat passes straight from the flame, through the metal, into the water or food inside. When you grab the pan’s handle after a few minutes and yelp in surprise, that’s conduction at work again—the metal carried the heat from the base up to the handle.

Metals are strong conductors, which means they pass heat quickly. That’s also why most insulators, like the stoppers on thermos flasks or rubber handles on pots, are made from materials with very low heat conductivity. These materials slow down the flow of heat, keeping hands and drinks safer.

For a clear collection of everyday conduction examples, you might like to check out this informative breakdown: Heat Transfer – Conduction, Convection, Radiation.

Convection: Moving Heat with Liquids and Gases

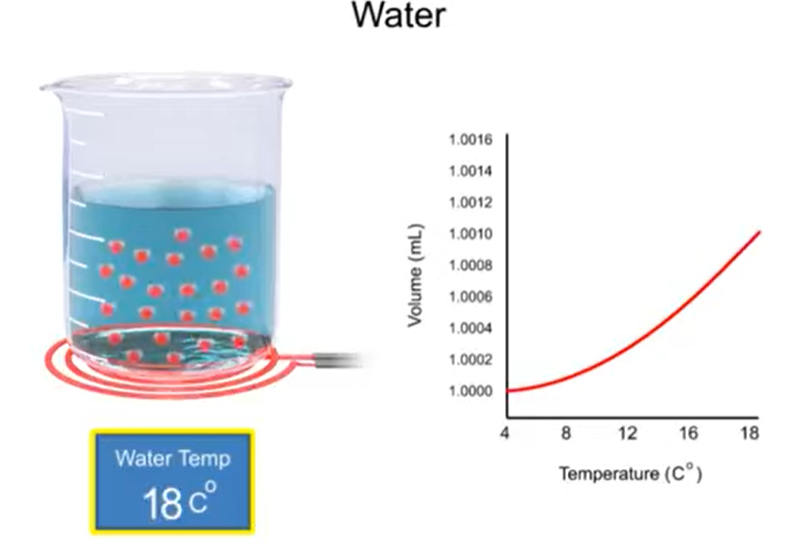

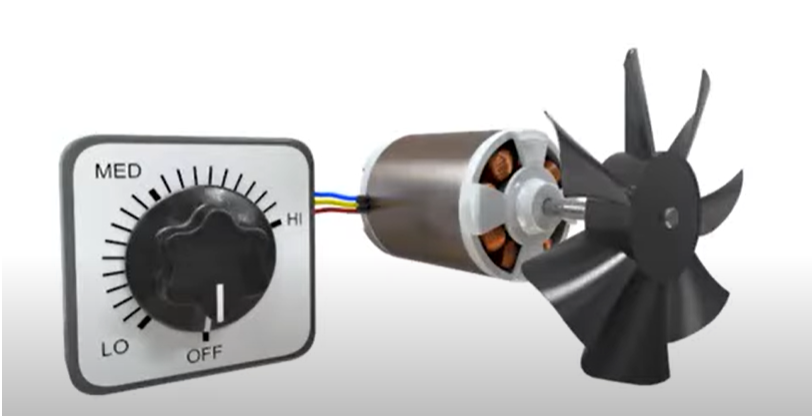

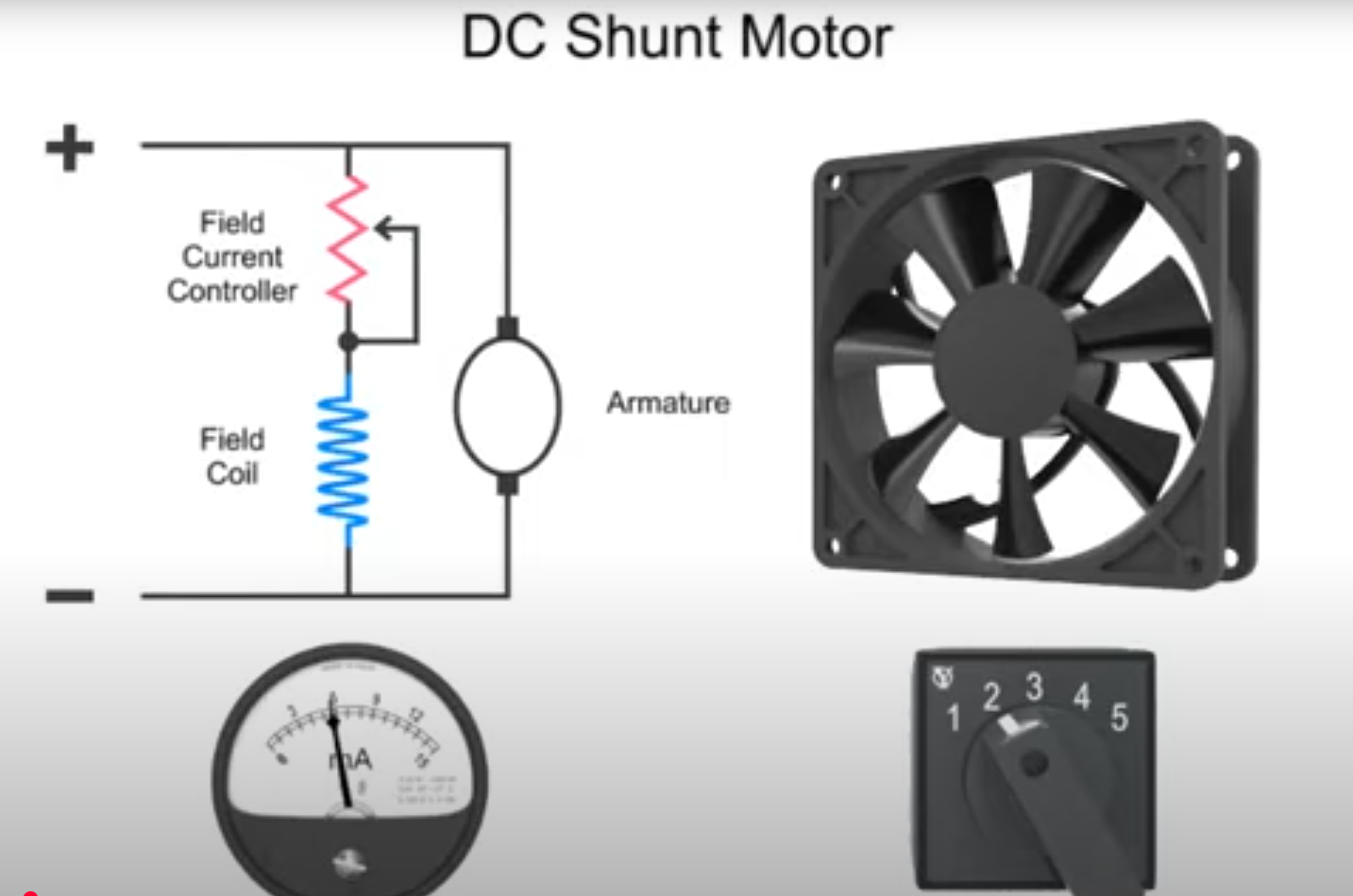

Convection describes the way heat moves through fluids, including both liquids and gases. It’s less about contact between objects and more about movement inside the fluid itself. Imagine heating a pan of water on the stove: the water at the bottom, closest to the heat, warms up first and rises to the top, while the colder water at the top sinks down. This creates a constant circulation, often called a convection current.

You can feel this effect on a breezy day, as moving air transfers heat more rapidly from your skin. It also explains why soup stews evenly or why heaters work faster with a fan.

Radiation: Heat Without Touch

Radiation is a way heat moves that does not need contact or even air as a medium. Heat travels as invisible waves directly from a source and can move through the vacuum of space. On the stove, the flames radiate heat in all directions. If you’re near the pan, you feel a gentle warmth on your skin—this is radiant heat.

In another everyday case, a hot mug left on the counter will cool off partly because it radiates heat into the surrounding air even if nothing touches it directly.

You can compare all three processes in common settings by visiting this page: Conduction, convection, and radiation – BBC Bitesize.

Real-World Examples of Heat Transfer

The science of heat transfer shapes much of what we do daily. Here’s how the three processes play out in real life:

- Cooking on a stove: All three forms of heat transfer come into play when heating a pan of water. The flame radiates heat. The metal pan conducts this energy from the burner up to its rim and handle. Meanwhile, convection circulates the hot and cold water in the pan.

- Cooling coffee on a countertop: Leave a hot mug on a cold surface and its temperature drops because of conduction (from mug to table), convection currents (in the liquid itself), and radiation (from mug to air).

- A thermos at work: A well-designed thermos limits all three pathways to keep your drink hot or cold.

If you’re keen on more examples that you can spot at home or outdoors, there’s a handy summary at Three types of heat transfer.

Preventing Heat Loss: How a Thermos Works

Not all containers are created equal. A thermos flask is carefully built to trap heat, limiting its loss by conduction, convection, and radiation. Let’s look at its smart design features:

- Vacuum insulation: Between the inner and outer walls, a vacuum acts as a strong barrier. No air means there is almost no chance for convection to carry heat away.

- Silvered glass walls: These shiny surfaces reflect radiant energy back into the bottle, making it tough for heat to escape as radiation.

- Low-conductivity stopper and glass: The materials chosen for the stopper and outer shell don’t conduct heat very well, which slows down any heat leakage by conduction.

Though a tiny bit of heat escapes through the neck and stopper, the design is so effective that it keeps coffee piping hot (or water cold) for hours. If you want to see how this concept is explained with visuals, take a look at the section on heat transfers and vacuum flasks from BBC Bitesize.

Heat Capacity and Phase Changes in Water

Heat capacity tells us how much energy it takes to raise the temperature of a given amount of material by 1°C. Water is remarkable here because its heat capacity and energy requirements change depending on whether it’s ice, liquid, or steam.

Heat Capacity of Water in Different Phases

| Phase | Heat Capacity (cal/gram/°C) |

|---|---|

| Ice (solid) | 0.5 |

| Water (liquid) | 1.0 |

| Steam (gas) | Varies, but much lower |

- Ice: Takes just half a calorie to warm 1 gram of ice by 1°C.

- Liquid water: Needs 1 calorie per gram per degree, so twice as much energy as ice.

- Steam: The heat capacity drops but, by this point, a lot more energy has already gone into phase changes.

The Energy of Phase Changes

To go from ice at an extremely low temperature all the way to steam, water needs a boost through several stages. Here’s what happens step by step:

- Warming the ice to 0°C: If we start with 1 gram of ice at -273°C (absolute zero), raising it to 0°C takes about 140 calories (0.5 cal/g/°C × 273°C).

- Melting the ice (heat of fusion): Transforming 1 gram of ice at 0°C to water at 0°C takes 80 calories.

- Heating water to boiling: Raising that gram of water from 0°C to 100°C = 100 calories (1 cal/g/°C × 100°C).

- Boiling the water (heat of vaporization): Turning 1 gram of water at 100°C into steam at the same temperature takes 540 calories.

Add it up: 140 + 80 + 100 + 540 = 860 calories to turn 1 gram of ice at absolute zero into steam.

For more details about the science and real values behind heat capacities, see the helpful lesson at Specific heat, heat of fusion and vaporization example.

Conclusion

Every warm mug, toasty meal, or chilly drink depends on how heat moves through and around us. Understanding conduction, convection, and radiation reveals why pans heat unevenly, why thermos bottles keep chai hot for hours, and how cold air seems to steal warmth so quickly in winter.

Knowing these basics empowers anyone to pick the right pan, use kitchen tools wisely, or make the most of an insulated bottle for travel or school. As you go about your day, look for examples of heat transfer in action—from the kitchen, to the park, to your daily commute. Science is all around you, often right at your fingertips.

If you’re interested in exploring these principles further—or want to see how heat transfer shapes energy use, cooking, or even weather—explore more explanations and examples at pages like Heat Transfer – Radiation, Convection And Conduction.

Let your curiosity heat up, and notice the power of thermal science in action the next time you boil water or pour a cup of coffee!